SMT-V 6.5, "Melodic Language & Linguistic Melodies: Text Setting in Ìgbò" by Aaron Carter-Ényì and Quintina Carter-Ényì is now available at www.smt-v.org.

Abstract:

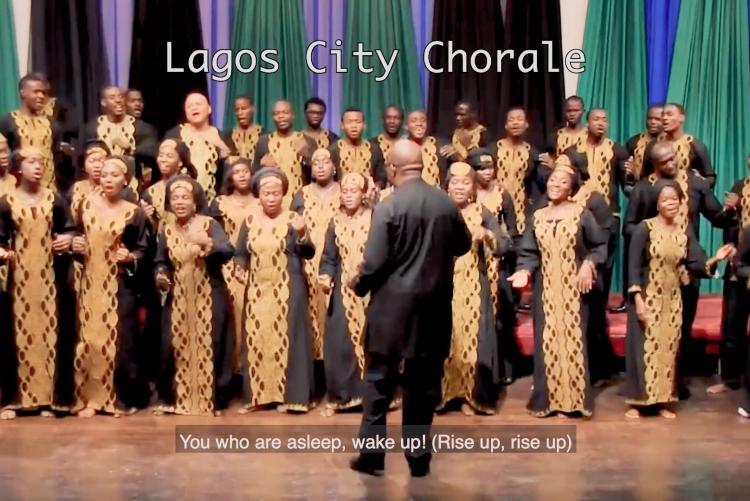

There are no other sense-altering aspects of culture that equate with language’s effect on aural perception (hearing). Increased sensitivity to pitch is a cognitive characteristic in the 60% of the world’s ethnolinguistic cultures that speak tone languages (Yip 2002). Lexical tone is a pitch contrast akin to the contour of a melody that distinguishes between words. An example is [íké] (high-high, like a repeated note) and [íkè] (high-low, like a falling interval) which forms a minimal pair between the Ìgbò words for strength and buttocks. Being a tone language speaker also impacts ways of musicking, especially singing. This is the case in sub-Saharan Africa, where “language and music are tied, as if by an umbilical cord” (Agawu 2016:113). A favorite tool for evangelism among 19th- and 20th-century European missionaries in West Africa was to translate European hymn texts into the language of the missionized and teach them to sing the translation to the original hymn tune. An example included in the video is “All hail the power of Jesus’ name” which is often sung to the Coronation hymn tune by Oliver Holden (1792). Unfortunately, early missionaries would translate the texts metrically (to preserve the number of syllables) but had no understanding of the necessary tone.

Because of the link between lyrics and melody in tone languages, composers of vocal music in tone languages have argued that one should not compose vocal music in isolation from text or vice-versa. In 1974, Laz Ekwueme, a doctoral advisee of Allen Forte, published an article on Ìgbò text setting and harmonization. In addition to parallel harmony, Ekwueme recommends staggering text (as in European polyphony or African call-and-response) and using alliterative sounds (vocables and onomatopoeia) in subordinate voices.